The Center Court inside King Saud University Indoor Arena is painted the pale purple of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), pioneers of gender equality in sports. Led by Billie Jean King, the organization convinced the US Open to award equal prize money for male and female players in 1973—making the tournament the first sporting event to do so. Several of the highest-paid female athletes are tennis players. WTA matches are also given relatively even media coverage, allowing for equal distribution and access to the women’s game. In 2023, 3.4 million viewers tuned into the US Open women’s singles final, whereas 2.4 million watched the men’s. Some WNBA matches, in comparison, aren’t televised at all.

However, a single word rests behind the court’s baseline, printed in sterile white: Riyadh. That’s the capital of Saudi Arabia, which ranked 126 out of the 146 countries evaluated in the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Gender Gap Report.

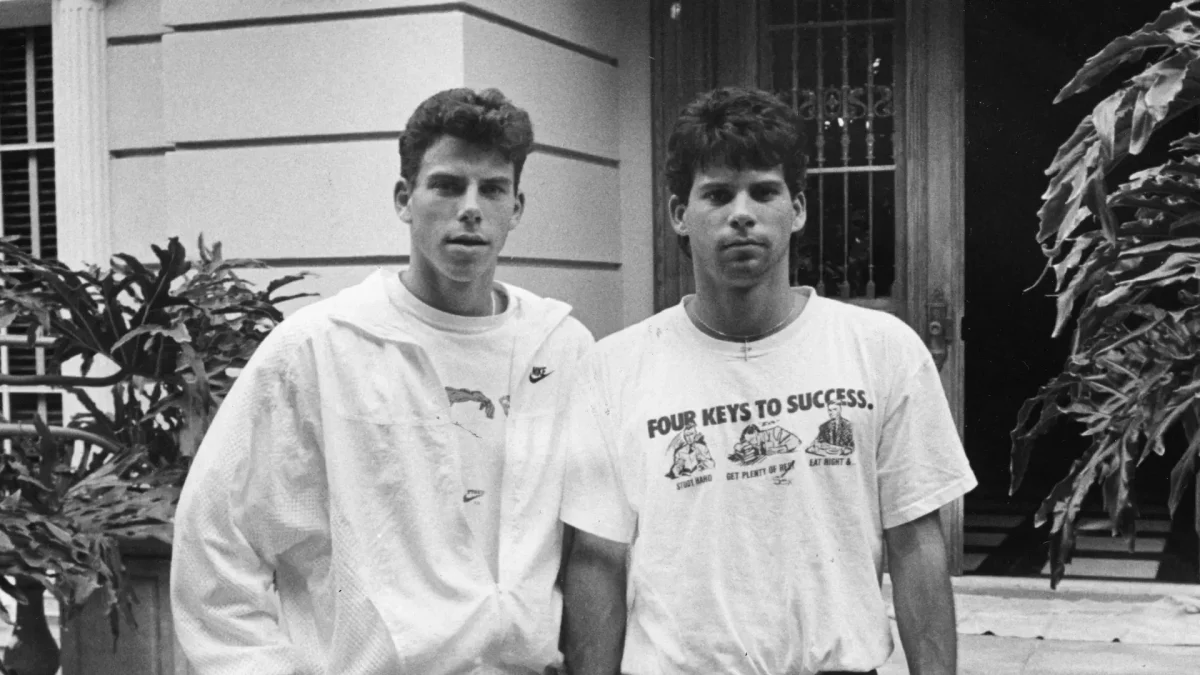

The WTA Finals, the most prestigious event in tennis after the Grand Slams, concluded on November 9. The organization spent four years searching for a long-term host for the Finals before it settled on Saudi Arabia. The deal was met with sharp pushback before it even went through. In an opinion piece for The Washington Post, legendary players Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova claimed that Saudi Arabia hosting the finals “is entirely incompatible with the spirit and purpose of women’s tennis and the WTA itself,” adding that the move “would represent not progress, but significant regression” in the organization’s work on women’s equality. They accused the event of being an act of sportswashing.

What is Sportswashing?

When a company, government, or country uses sporting events to improve (and distract from) their reputation, they’re engaging in sportswashing. Although Western nations have also been accused of this practice, the most notorious offenders are authoritarian countries with poor human rights records.

For example, Russia and Qatar heavily restrict freedom of speech and LGBTQ+ rights, but both countries hosted the World Cup in the last six years. Russia used forced labor to build the stadiums. Qatar, meanwhile, hired tens of thousands of migrant workers, who performed manual labor in the country’s blistering heat. They lived in overcrowded and unsanitary labor camps and did not receive their promised pay. At least 21 workers died in Russia. Over 6,500 died in Qatar.

Sportswashing pits fans’ love for their team, players, and sport against their morals. So, despite outrage over Qatar’s working conditions (and Qatar hosting in general), more than 3.4 million people attended the World Cup, while a record 1.5 billion people watched the final on television.

Saudi Arabia’s Role

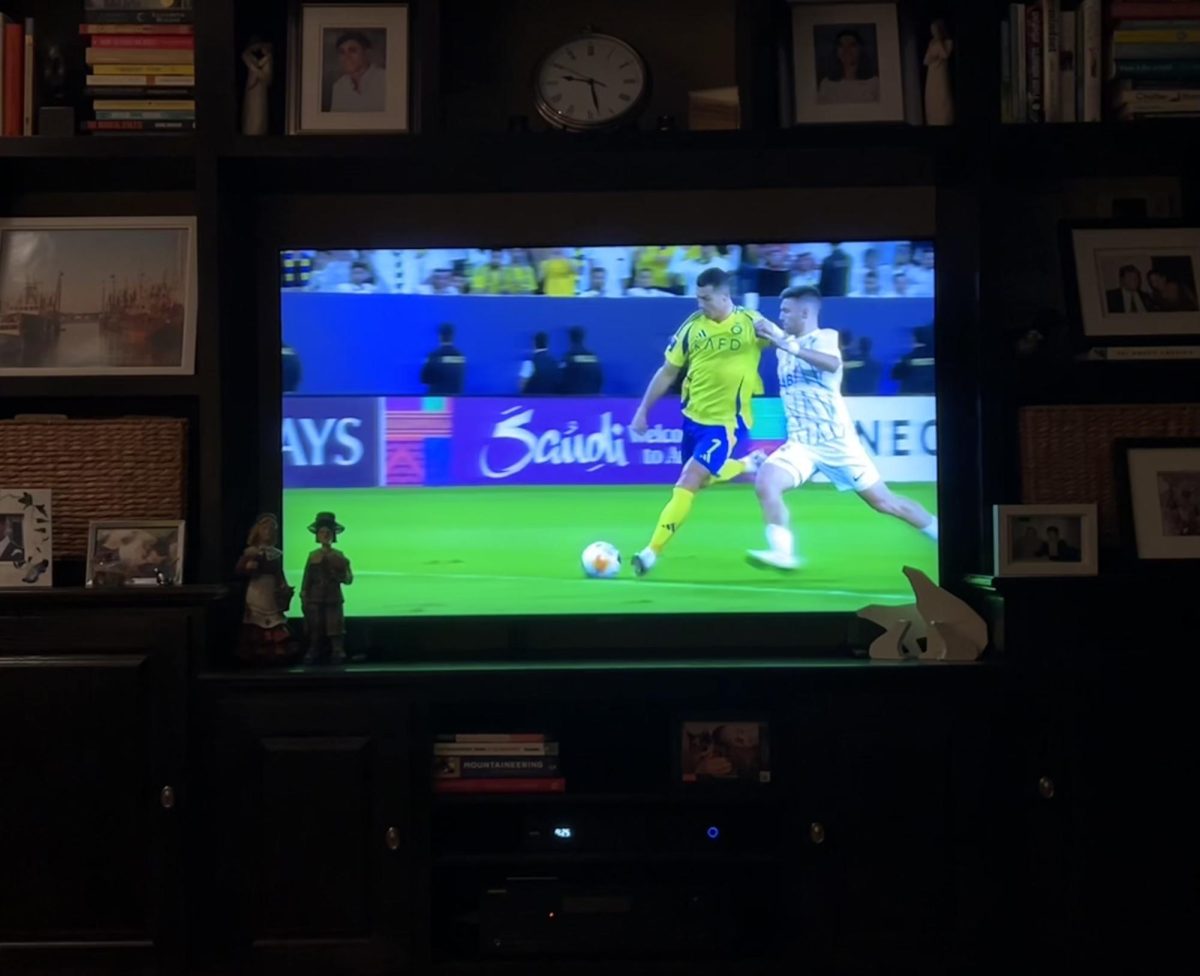

Saudi Arabia is the country most associated with sportswashing. They’re involved in several sports. The kingdom’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), which has around $930 billion in assets, is the majority owner of the Saudi Pro League’s founding four teams. One of those teams is Al Nassr, which swooped up several players from the Premier League, most notably Cristiano Ronaldo and Jordan Henderson. Meanwhile, the PGA Tour, the DP World Tour, and the PIF are currently negotiating a merger as more pro golfers leave the PGA for LIV Golf, another PIF project. An F1 Grand Prix takes place in Saudi Arabia, as do a variety of WWE events. The kingdom hosts 85 major events, and is currently bidding for the 2034 World Cup.

What would tempt a player to join a Saudi league? Money plays a substantial role. Ronaldo’s contract with Al Nassr earns him over $228 million per year, making him the highest paid soccer player in 2024. Two weeks before the WTA Finals, Riyadh hosted the Six Kings Slam, an exhibition tournament featuring two tennis legends, three current stars, and Holger Rune. Exhibition tournaments are informal, played for charity or fun, with no effect on a player’s ranking. The prize for winning the Six Kings Slam was $6 million—a far greater amount than players receive for winning a Grand Slam. For comparison, the 2024 US Open champions acquired $3.6 million.

A dark reality lies behind the big names and the big paychecks. There’s been “some significant social reforms” in the realm of women’s rights, such as allowing women to drive and attend soccer matches in 2018. However, under the Personal Status Law, a woman is required to have a male legal guardian, and must have their guardian’s consent to be married. The woman’s husband subsequently assumes guardianship over her. Plus, women cannot attend said soccer matches without a male guardian.

Homosexuality is illegal in the kingdom, and the US State Department reports violence against members of the LGBTQ+ community. In fact, in their most recent annual report on the kingdom’s human rights record, the State Department said “there were no significant changes to the human rights situation in Saudi Arabia during [2023].”

When it comes to civil liberties, Freedom House gives Saudi Arabia an overall grade of 8 out of 100. Citizens exercising freedom of speech and expression, whether by advocating for human rights or criticizing the absolute monarchy, are arrested and sometimes tortured. Notably in 2o18, journalist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered in an “operation approved by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.” Khashoggi’s assassination was a stark symbol of concerns over freedom of the press.

In addition, Saudi Arabia’s airstrikes on civilian targets in Yemen have been characterized as war crimes.

Can Sports Make a Difference?

Government officials deny that they use sports to cover up corruption. During an interview with the BBC, Saudi Arabia’s sports minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Turki Al Faisal said “that [the kingdom’s] unprecedented investment in sport… is to help inspire a youthful population to take up physical activity and exercise, open the country up to the international community, boost tourism, create jobs and provide sports federations with growth potential.”

Athletes and government officials often cite increasing youth participation in sports as a major motivator for getting involved in Saudi leagues. Coco Gauff, who won the WTA Finals, helped teach a girls’ tennis clinic in Riyadh ahead of the event. “That’s why I wanted to come here,” she said. “There’s never been a professional women’s tennis event here. And just to show young girls that their dreams are possible.

“I hope that when I retire there’ll maybe be a Saudi Grand Slam champion or WTA Finals champion. And I think if that happens, then I did my job, and the rest of the players who played the first event here did their job.”

Ahead of the event, Gauff admitted she initially had reservations about playing in Saudi Arabia, but expressed hope that bringing the Finals to the kingdom would spark incremental progress in women’s and human rights.

Evert and Navratilova believe, however, that “there should be a healthy debate over whether ‘progress’ and ‘engagement’ is really possible, or whether staging a Saudi crown-jewel tournament would involve players in an act of sportswashing merely for the sake of a cash influx.”