The Scam of the Success Aesthetic

The temptation of aesthetics is inherent to its purpose, to attract viewers and sell a product, but what happens when aesthetics are applied to an abstract concept such as success? The rise of the 21st century marked the popularization of the internet and social media, a forum where aesthetics could thrive. People before defined success with shiny cars, designer clothes, and wads of cash. However, social media’s proposed “success aesthetic” seems to be a different entity altogether. Instead, the success aesthetic seems to materialize as “rags to riches,” with deep rooted flaws in its presentation with more of an appeal to younger people, specifically women, trying to brand themselves, who are not exactly sure what they want to pursue, other than money.

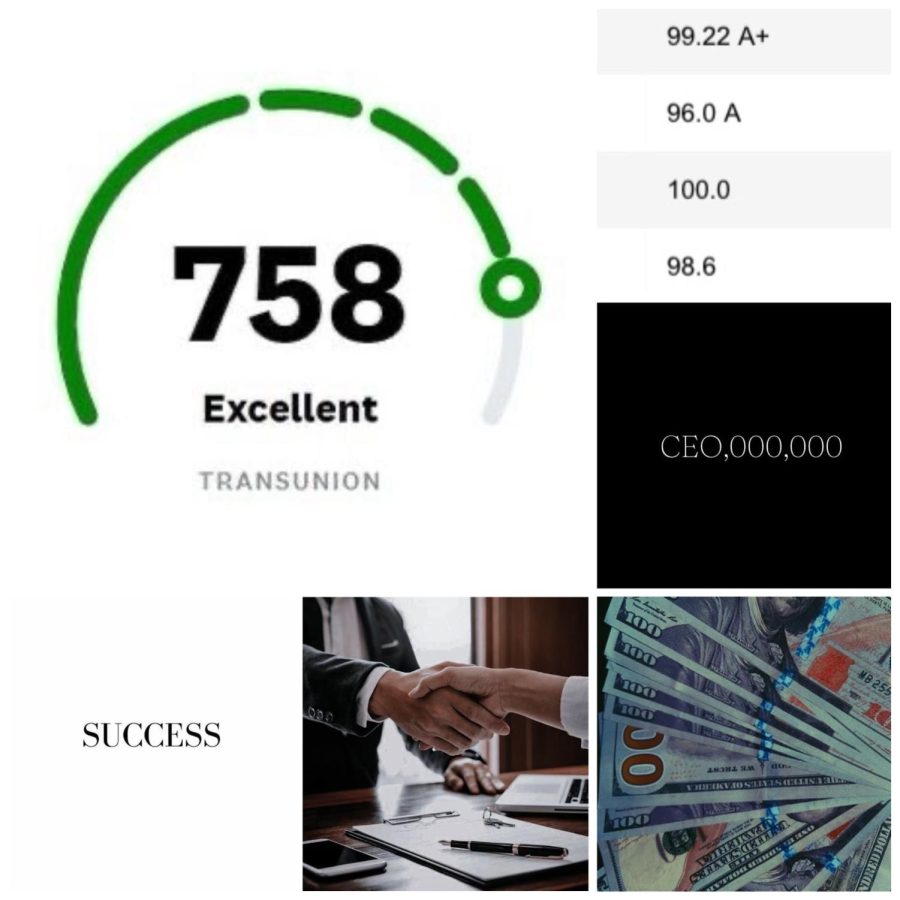

The notion that there is an aesthetic version of success is dubious in itself by claiming a level of uniformity. Success means CEO, city life, big meals, generic beauty, lavish parties, high heels, designer suits, gym-grind, private planes, outstanding credit score, and straight As, according to the pictures. This narrative is the result of several false notions. A.) Good grades always set you up for success, B.) All successful people are millionaires, C.) Parties, planes, and property are measures of success, (along with a near impossible credit score for college grads).

But who are the stakeholders in offering such a narrative? There are several potential entities; tech giants being the most influential, who greatly benefit from young people being drawn to the lucrative potential of new jobs created by social media companies and the natural prestige provided by saying, “I work at Google.” The success presented has distinct corporate feel, clean and modern, in the same tone presented by most of the entertainment industry, that women have look and act a certain way to be a boss.

To make sure my gender, age, and current internet history did not influence my research, I created a Pinterest account, an app commonly used to create vision/aesthetic boards, on my Dad’s iPhone. For anyone from artsy preteens to “creative” moms, it’s social media with less of the social aspects like influencers and likes.

Identifying as non-binary and 36, and disabling any data sharing, I searched “success aesthetic,” and what popped up at first glance seemed to be innocent enough. Quotes like, “I know what I want and I’m gonna get it” and “millionaire loading” in various fonts and backgrounds send messages similar to that of the Amazon Echo Daily Affirmations, which I somehow turned on in September to start immediately after my alarm, which triggers the irreversible cycle of waking up to a loud automated voice telling me to, “choose happiness and attract love,” while I’m just trying to find the motivation to make it to the coffee machine 10 feet away; general, unhelpful, and obvious.

The deeper nature of the aesthetic doesn’t rear its head until more scrolling, when you realize the specific type of people depicted in photos of this aesthetic: beautiful white women drinking champagne while overlooking Paris or New York. I had to scroll past approximately 180 photos (I counted, but alas I am not good at math), to get one image depicting black women, posed similarly to the other women, walking out of nice cars, bags from designer shops, and jewelry worth enough to buy a house in Arizona. Almost a metaphor for the United States, although success has no race or gender, there are types of people who are more apt to achieve it. Why do women have to be beautiful to be successful regardless of race, to achieve the “success aesthetic,” and why does an aesthetic based on the notion of working hard to be a “CE0,000” never depict anyone actually working?

The “success aesthetic” is a perfect demonstration of using pictures of an end-product to convince consumers to buy into the subliminal advertising of a false narrative. As Professor Jonathan E. Shroeder said in an academic editorial piece published by Sage Publishing, concerning images and aesthetics in advertising, “pictures cannot be held true or false,” in the ways that statements can in marketing, if a woman looks happy drinking champagne and exudes the 24k glow of richness, who are we to say she is not the “success aesthetic.” Such an airtight argument for “aesthetics” is dangerous, it eludes debate and reform because it bases its argument in the ageless roots of capitalism, which favors private industry builders, and puts them on historically high pedestals.

This is not to say that hard work is irrelevant to success, but rather the aestheticization of it is impossible. As someone who is always weary of aesthetics, the current trend of turning a concept into one is concerning. With starting a new year, it’s tempting to buy into the success an irrefutable appeal to vanity, but it’s important to remember that most aesthetics are created to sell something, if not a product, a belief system.