A Closer Look: René Magritte’s surrealism

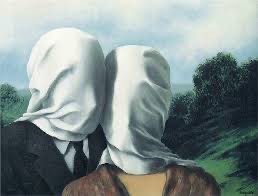

The Lovers II.

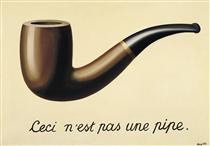

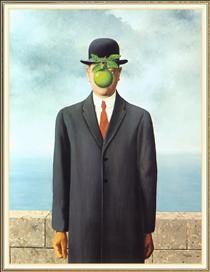

René Magritte’s The Lovers II is trauma and love on canvas, and a work that demands thought of its viewers. René Magritte, a Belgian artist, is a household name when it comes to surrealism. known for The Son of Man, The Treachery of Images, and various other peculiar masterpieces. Setting apart The Lovers II is most prominently the subjects themselves, almost perfectly average lovers apart from their veiled features. So one had to wonder why the change in tone of this painting? It lacks the poignance of blatant whimsy other works of fruity or backwards men, instead the painting has a mysterious peculiar tone.

Art without limits of aesthetics or reason, surrealism, was the staple of René Magritte, and this intriguing concept outlives its artists. To first understand The Lovers, it is necessary to understand its origins, and more specifically its derivation from quantum mechanics. Usually arts and sciences could not be viewed as more different like night and day, emotional and rational, yet surrealism is heavily in coexistence with the foundations of Bohr’s quantum mechanics. Both Bohr and Magritte were both inspired by Henry James’s Principle of Psychology. The basis of the book’s teaching is that streams of thoughts are unpredictable, and it is impossible to see the part of thinking where one thought reaches another. This parallels a Quantum Jump, when an electron transition in an atom is instantaneous, unobservable. Just as when two bodies of water meet, they become indistinguishable from one another, the meeting itself is instantaneous, invisible.

Such is seen in the faces of the lovers, their expressions, the emotions cannot be seen, yet they are committing an emotional act. Both Bohr and Magritte occupied their fields in the 1930s and 40s, yet quantum inspiration is not the only subtle contributor to the work, but also Magritte’s traumatizing adolescent years.

Magritte was adamant that no connection between the painting and his mother existed, yet the similarities cannot be denied. In 1912 Magritte’s mother died of suicide by drowning in the River Sambre in Belgium. She had attempted many suicides before this, and at one point she was so prone to self-destruction Magritte’s father confined her to her own bedroom. When Magritte’s mother resurfaced, her dress was covering her face, reminiscent of that of the Lovers. Magritte was 13 at the time, making his psyche particularly vulnerable to any traumatic events. Perhaps The Lovers series was, even if not intentional, a tribute to his mother. Tragedy seems to be a common thread with exceptional artists such as Vincent Van Gogh and Edvard Munch who also had melancholic early years.

Or perhaps it is a contrast to his earlier works. Magritte began with many oil paintings featuring nude women, but here the woman is so covered her face is hidden. The new depiction of women could be a coincidence, or a sign of progression to paintings that break away from previous object depictions in more and more extreme ways.

But by far my personal favorite theory is that the veil represents the barriers between the closest of lovers. No matter how well people know each other, there is always a barrier between their perception of you and who you really are. As Donna Tartt, in the book The Secret History wrote, “Even more terrible, as we grow old, to learn that no person no matter how beloved, can ever truly understand us.” No matter how many stories one shares with others, no one will ever experience life as you did, no one will experience looking through the world with your eyes.

Far more likely, the veils, the painting, the lovers mean nothing. As Magritte often said about his paintings, “It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable.” But in fact, as Magritte most likely knows, everything means something, as we perceive anything, we are simultaneously giving it meaning. Interpretation is instinctual as one journeys through reality, to give existence substance and make living a manageable task.

Notice how the painting is gray-toned, like a memory, a dream, or a reflection. Differing from The Son of Man and The Treachery of Images, this is distinctively muted in its oddities. But what is particularly striking about this piece is its prequel The Lovers I. The painting features the subjects of The Lovers II, but they are faced towards the audience. In a subtle sense, however, the woman is looking forward, but the male is looking at the woman. They are also in front of a field whereas in the latter they are in a bedroom. They have also switched positions in the painting. It can’t be avoided that even though they appear to be a content couple, the veil gives the appearance of individual suffocation for both parties. The male goes from standing behind the female to being at the forefront, perhaps a commentary of the norms of the time. The clothing of the subjects are in correlation with the long due prosperity in Belgium during the time before the depression set in, with the man and woman wearing clean, fashionable clothes.

The Lovers II is perhaps in its surrealism the most realistic artistic interpretation of romance. The pitfalls, the confusion, the struggle with individuality and barriers. The painting is no doubt beautiful no matter its ghastliness. Lovers II is currently located in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, while The Lovers I is located in the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. A world apart, the mystery of The Lovers perplexes generation after generation, century after century.