DHS literature: Reading through a feminist lens

Novels like The Scarlet Letter, Moby Dick, and Of Mice and Men, despite differing genres and story plots, all bear one similarity: the gender of their authors. DHS’s English curriculum has a plethora of books that cover most periods of history, from Elizabethan times to the Great Depression in America to Romanticism and more.

The majority of the stories we read are written by men, in the point of view of men, or have an equally important male counterpart getting as much paper space as the protagonist. In American literature, there is a seemingly heftier amount of male authors than females who write novels as well.

There are few established female writers whom we commemorate in our curriculum due to the lack of respect and attention they were given in the past. Aside from some British literature, women who write and are respected for their writing, are a rare commodity. From the pressure of society, most female authors had to use pseudonyms, or false names to disguise themselves in order to publish their work.

One book in particular that most students enjoyed in our middle school curriculum was The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton, a teenage girl who, at the time, used her initials to get published because of the struggle her gender imposed in the world of literature.

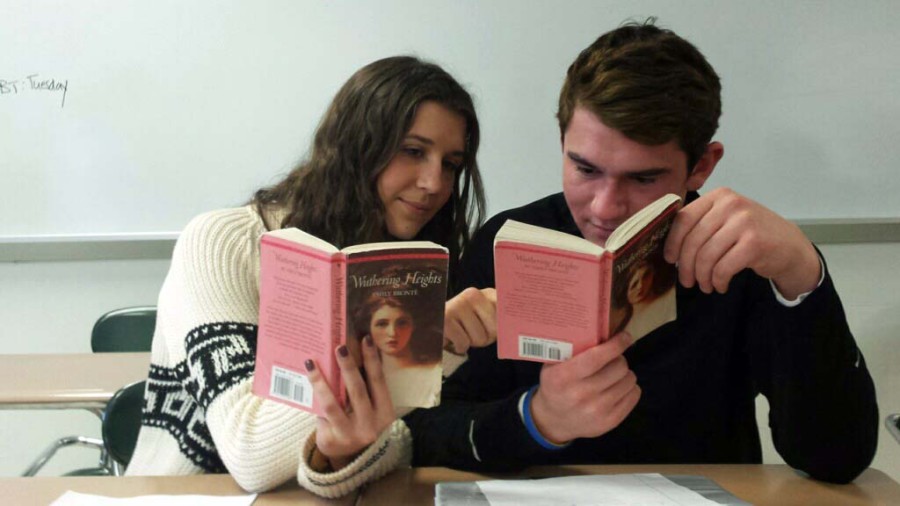

Another example is Wuthering Heights – Emily Bronte used a pseudonym to get published.

In the four and a half months of English class, no matter what course, required reading takes up a chunk of time along with vocabulary and essay writing. Most of the novels we read barely, if not at all, pass the Bechdel Test.

The Bechdel Test, a gender bias test established by Liz Wallace and later coined from cartoonist Alison Bechdel, requires two female characters in any form of media to talk to one another about a topic that doesn’t center around men. Stories like Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck and Macbeth by William Shakespeare don’t even have a second female character that survives throughout the novel, never mind hold a meaningful conversation.

There is also a struggle with differing stories and lives that take place in the world of books. Diversity among novels is essential to amplify students’ learning experience and to aid in their development to becoming more versatile students and citizens. To ensure that the students of DHS have a far more well-rounded perspective of personal experiences and fictional metaphors, there needs to be a diverse group of books that we read.

Americanah author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie mentioned in her TEDTalk, “The danger of a single story,” that focusing on one story can help form stereotypes in other groups of people and “make one story become the only story.”

A vast majority of the novels we’re required to read isolate the female characters into common tropes that have been around for decades. This umbrella term for “she” can fit the mold as a matriarch, kind and soft spoken; a femme fatale, beautiful and dangerous; platonic love, a friend but never anything more; or a young and naive girl with her head in the clouds. These novels that center on males ignore the fact that all of these traits can live in one woman, and they fail to show the depth and complexity that breathes in each female character.