“It’s a governing body that basically determines the validity of a high school diploma. That’s why students should care about it.”

That’s how DHS Lead Science Teacher Arlyn Larson described the New England Association of Schools and Colleges, better known as NEASC. Every 10 years, New England high schools are due for a NEASC evaluation that will decide whether or not they receive an accreditation from the organization. (DHS was last evaluated in 2012, but COVID caused many schools’ evaluations to be delayed.) NEASC makes sure the schools meet five standards related to learning culture, student learning, professional practices, learning support, and learning resources.

Mrs. Larson is serving on this year’s DHS-NEASC Steering Committee, along with Principal Ryan Shea, Associate Principal Rachel Chavier, and lead social studies teacher Jeff Reed. The committee oversees the entirety of the accreditation process.

NEASC’s website describes an accreditation as “a globally recognized standard of excellence” that “attests to a school’s high quality and integrity.” If students graduate from a school that fails to be accredited, it could seriously hamper their abilities to get into college.

However, for a school to be denied accreditation, the situation has to be dire. “Schools that are not accredited have major deficiencies, and in many cases the state has to then intervene to get things back on track,” Mrs. Larson said.

There’s always room for improvement, though. “The overall goal,” she said, “is to become a better school as a result of this process.”

The accreditation process begins with a self-study, happening this fall. Compiled by faculty writers—including history teacher Lauren Enoksen, computer science teacher Bridget Weinert, art teacher Morgan Bozarth, special education teacher Kathryne Moniz, and librarian Meaghan Tully—the self-study allows DHS to evaluate itself on whether the school meets NEASC’s standards.

NEASC’s standards are very different from the state’s standards. The state only sets standards for the curriculum, but “the curriculum is just one tiny piece of NEASC,” Mrs. Larson said. NEASC requires a wider portrait of a school, as reflected in the self-study.

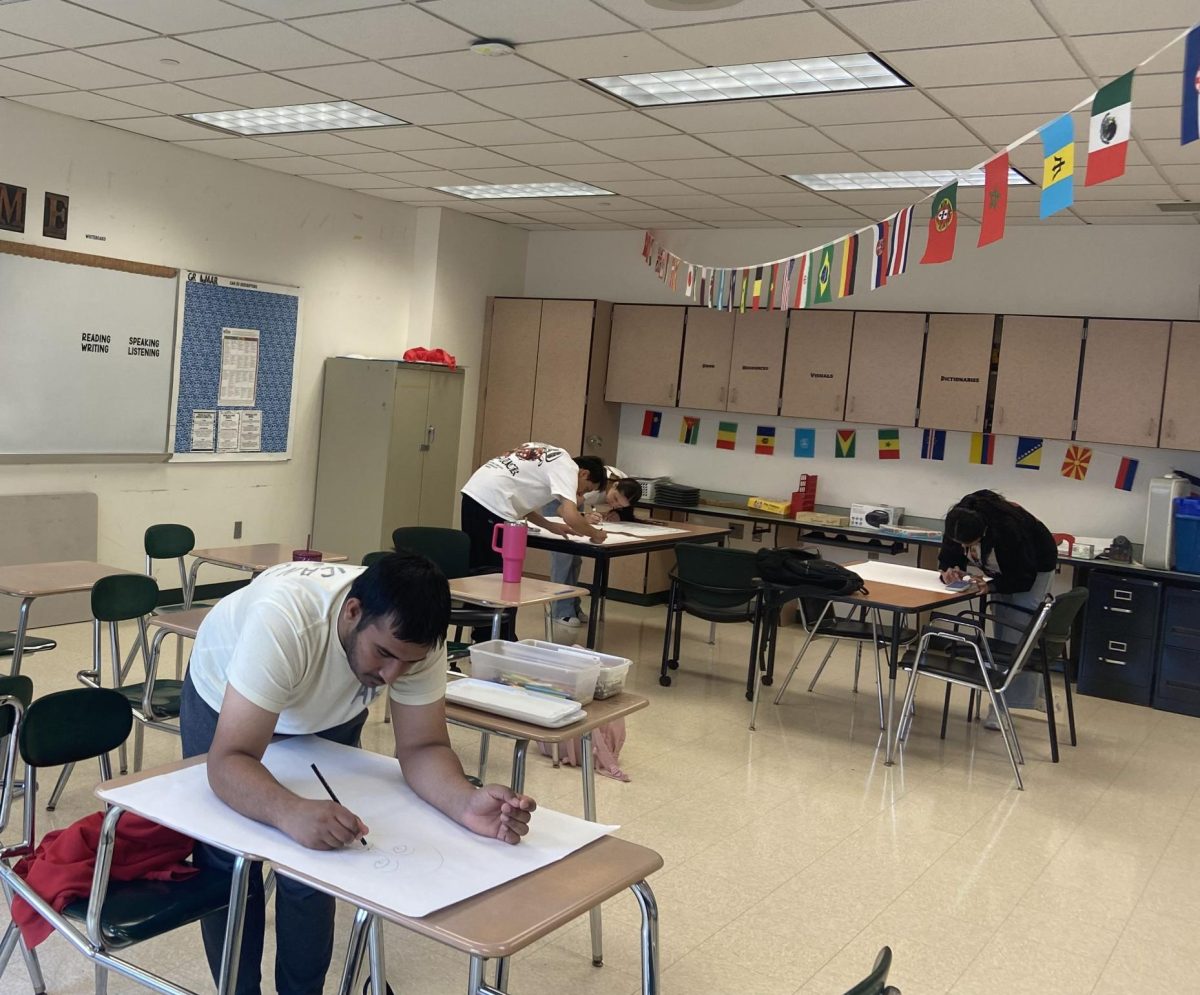

“The self-study basically takes a deep dive into the practices of DHS,” Mrs. Larson explained. “It looks at everything from building safety, curriculum, instruction, assessment, our portrait of a learner, our school improvement plan. Do we have the resources to teach? Are we offering clubs? Are minority students represented?”

Those questions are answered in part by the DHS faculty, student body, and parents. Each group will be sent a survey asking for their opinion on the topics listed above, among others. Students were given the link to the survey during the October 3 advisory meeting, and Mrs. Larson stressed the need for “full participation.”

“Those three avenues provide us with feedback that helps us write our narrative report,” she said.

After the self-study is complete, DHS will start making changes to their school environment to address any shortcomings. Then, the study will be sent to NEASC, who has a month to review it. In March 2025, NEASC will send a visiting team to confirm the accuracy of the self-study—or, make recommendations for gaps and omissions.

The visiting team is composed of six “experienced educators” from districts across New England, according to the organization’s website. Although they volunteer to be on a team, the members “are carefully selected and trained for each school visit.”

Most likely, the team will interview students—as a group, though, rather than individually. During previous evaluations, a team member was paired up with a student and shadowed them for an entire day. However, Mrs. Larson doubts this practice will return due to time constraints. “They’re only going to have a short period of time throughout the day,” she said. “I’m guessing it’s going to be about an hour and a half where they’ll have availability to be in classrooms. So, at this point, I’m not entirely sure if they’re going to be paired, or if it’s going to be a general quick in-and-out of certain classrooms.”

As a member of the Steering Committee, one of Mrs. Larson’s responsibilities is to “provide a welcoming experience for the visiting team.” This includes supplying hotel accommodations and food for the visiting team—all paid on DHS’s dime. “We have to make sure that they space a schedule of events, a space to work in the building—all that,” she said.

It doesn’t end there. After the visiting team leaves, DHS will have three to five years to revise any areas of concern pointed out in the evaluation or remaining from the self-study. In the spring of 2027, another team of around 12 people will visit DHS to ensure the school is making progress. “It’s quite a lengthy process,” Mrs. Larson said. “We have a lot of hard work to do right now.”