Senior Luke Nelson found that, on any given day at DHS, the cafeteria generates an average of 226 pounds of garbage. Food waste, styrofoam trays, and milk cartons pile up over the course of three lunch periods before being sent to the Crapo Hill Landfill—a facility that’s running out of space to hold Dartmouth and New Bedford’s trash.

Nelson wondered how much of those 226 pounds could actually be recycled.

For AP Research back in his junior year, Nelson investigated how students would respond to recycling efforts in the cafeteria. “A big thing with AP Research is addressing local issues,” he explained. “For example, other AP Research students dealt with stuff like cell phone policies and bacteria in the school. I thought, ‘Cafeteria issues are always big.’”

There is no recycling program inside the DHS cafeteria. A single recycling bin was placed in the cafeteria to kick off last school year, alone among the four trash bins stationed in each corner. “It was black, not clearly marked and it had a cover on it,” Nelson recalled. “Students didn’t really ever notice it because the trash cans were always closer.” The recycling bin disappeared as the year progressed. “I’m assuming that, once they didn’t really collect anything, they took it away.”

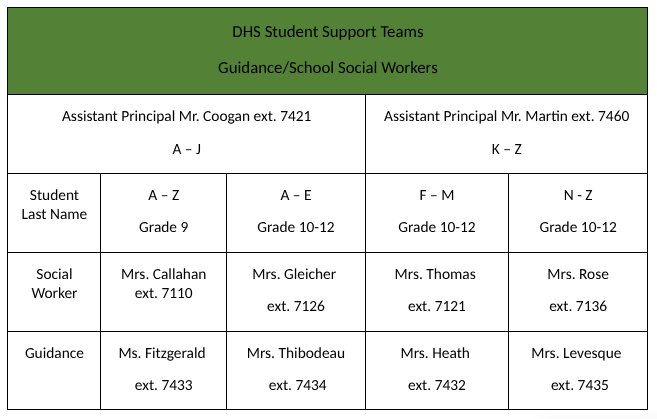

He ran into the same issue with his study. On the first day of his experiment, Nelson placed one blue recycling bin next to each trash bin. With the help of a website called Recycle Smart MA, created by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, Nelson drew up a flyer informing students of what items from the cafeteria can and cannot be recycled. He taped the flyers onto every table the following day. On the third and final day, students were informed about the location and purpose of the bins over morning announcements. Assistant Principal Graham Coogan delivered a similar message during the lunch periods using the cafeteria microphone. The goal was to see if continuously increasing the awareness and education around recycling would increase students’ use of the bins.

Over the course of the three days, Nelson collected a combined 2.5 pounds of recycling, which was “far under what I expected,” he said.

It wasn’t necessarily that the education initiatives weren’t working. Plastic salad boxes made up most of the 2.5 pound haul. “You normally don’t see those in recycling, but I included them on my flyer,” Nelson said. “So to see students actually read that and put those in there versus putting in random objects that aren’t even recyclable definitely shows that they are willing to recycle, they just might not have the [right] products.”

The last part was one of Nelson’s major findings. It wasn’t that students didn’t want to recycle—they couldn’t.

“Going into this, I initially believed that it was students that were at fault for not recycling, especially since this generation is regarded as being lazier or less motivated than others,” Nelson said. “But through my research, I really found that maybe it’s more so on the actual products used,” as very few of the items from the cafeteria are recyclable.

Those items are plastic bottles, aluminum cans, cereal boxes, and cracker boxes. Nelson was surprised to learn several items “that people commonly thought were recyclable, like napkins, utensils, and certain boxes like the milk cartons, aren’t.” Nelson stressed that, if recycling is to succeed at DHS in the future, there needs to be a comprehensive education program on how to properly do so.

Across the district, there’s been a gradual shift towards providing students with more sustainable materials. DHS packages some of their meals in cardboard boxes. The others are served atop those notorious styrofoam trays. Incidentally, DeMello Elementary School and the middle school repaired their washing machines and began piloting stainless steel trays last school year.

The limitation to these efforts is, unsurprisingly, money. According to Nelson, the upfront cost of fixing a dishwasher and purchasing steel trays exceeds the price of buying styrofoam trays in bulk. Nelson suggested fundraising to pay the expenses, but there’s also numerous grants, whether through the government or private organizations, to lessen the burden on school districts’ pocketbooks.

“We will make back the money. The question is when,” Nelson said. “It’s no secret that the high school is having to go under some budget cuts. Adopting a program such as this may not be the best choice for right now.”

Nelson theorizes that the cafeteria’s lack of recyclable materials isn’t the only reason why his bins didn’t fill up. Three out of the four items on Nelson’s flyer were drink containers, but many students are ditching single-use plastic bottles and aluminum cans for reusable options. “That was a limitation I discovered after I finished my research,” Nelson mentioned. “I don’t have an exact number of students that brought in reusable products. But simply just from viewing—at every table you could see a number of water bottles, whether they’re Yeti bottles or Stanley cups.”

What does this say about how Gen Z views sustainability? “I think it’s definitely something that’s underlooked,” Nelson said. “It does show that we kind of naturally contribute to a greener Earth.”

The situation in the DHS cafeteria is the same as where we left off last year: no recycling bins, a mix of styrofoam trays and cardboard boxes, no new environmentally friendly materials. But Nelson has hope that the efforts in the lower schools will travel to the high school. He thinks it’s smart to pilot the steel trays and other sustainable practices, such as composting at DeMello. “A younger audience is more susceptible to learning new things and new practices,” he explained. “DeMello has around 500 kids. If it ultimately failed in this high school where there’s roughly 1,000 kids, that’s a lot more money being wasted compared to 500. However, if it does work, you have a good sample size that you can educate as they go through the school years, so that when that class gets to the high school, they already know what to do.”