The Feminism of the Other Woman

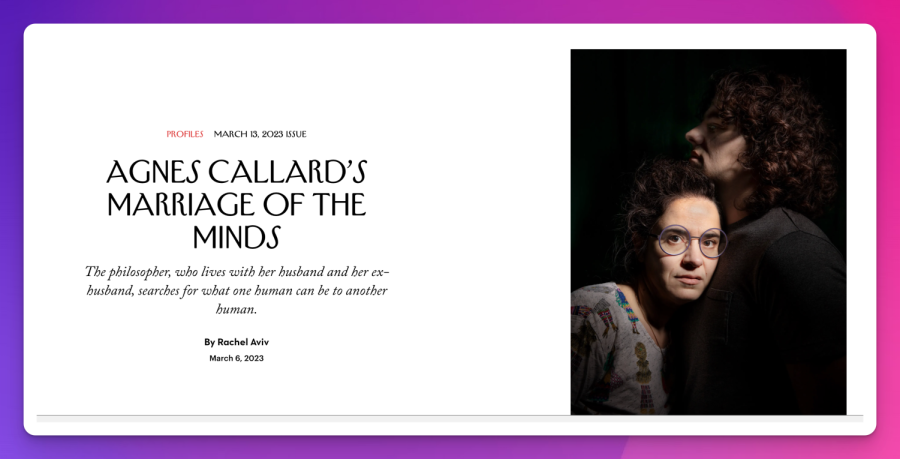

Recently, I found myself reading “Marriage of Minds,” an article in The New Yorker about the complicated marriages of philosopher Agnes Callard to other philosophers. The article left me with an inescapable sense of unhappiness: at the conventions of marriage, the downward spiral of close relationships, and the inescapability of the patterns 95% of lives seem to follow, all at once was suffocating. The article framed marriage as the death of love; I couldn’t help but find this ironic, and wonder what could have led to such a paradox. Was the simple solution to this dreary unhappiness synonymous with long term relationships, the polar opposite, was marriage the problem, or was the problem a gendered issue? I always thought, quite cynically, that if I lived with a partner for a long period of time, I would be peeved at the fact that they would be everywhere I am, and that my space would become our space, as if my life underwent a coup d’état headed by a serious relationship, that replaced democracy with communism.

Yet the more people I meet the more I realize we all strive for a sense of legitimacy to our existence, and this has a fundamental stake in our actions. Marriage is meant to be proof of love, a degree proof of education, a title like teacher, doctor, reporter, proof of identity. I find myself in a loop of trying to prove I am not the plethora of women-specific slurs, and at the same time, prove I couldn’t care less. Yet in the middle of a Ted Talk that seemed to be doomed from the start, when the black screen of death humbled my Ted Talk to a Ted, “what’s going on?” All I could think is why am I doing this, what am I trying to prove? Why am I always trying to prove something? For at the end of the day, life to be as disorderly and nonsensical as it often is? I felt ashamed afterwards, by the injustice I did for my passion on the topic and how paramount my point was to me, only to say only half of what I was meant to. Exactly how most pursuits start: with the best intentions, the higher the hopes, the greater likelihood of disappointment. And like many relationships, perhaps what took the enjoyment out of my talk was the pressure to prove; to prove my ideas were good enough, to prove I worked just as hard as anyone else, to prove people didn’t need to know me or like me to respect my ideas.

This thought process comes from one that women who are successful get a leg up somehow from their personality or something completely removed from any real skill, an idea I’ve struggled with; constantly wondering if I deserve what I get or is the so-called, “pretty privilege,” mitigating the leg work. People seem to deduce whether or not being a woman is a factor of favoritism depending on whether the woman is taken or not, because taken women are automatically “pure” and incapable of such callous misdeeds.

The fact that women who choose to be in a relationship are “taken,” is derivative of the fundamentals of misogyny, implying that women are forever in two stages since age fifteen, “taken,” or “other.” If you fall into “other,” you often find yourself in a cycle of overcompensating. By doing all the things a “bad woman” would never do; be a raging feminist with no time for men, be “one of the guys,” or simply work hard, anything that rejects alluring and often dangerous femininity. I see this in the various stages of the women I’ve grown up with and in myself, during which we tried to prove our legitimacy as colleagues and people. I find myself working to the bone to prove “I can do it,” only in return to be either envied or feared, or perceived as “secretive,” because I don’t wear my struggles on my sleeve. This process is dehumanizing, in the pursuit of proof I became a concept of what people think I am rather than an actual person. The pursuit of proof is a hydra, try to solve it one way, and two other problems materialize. It’s not to say I’ll stop working hard, I genuinely enjoy most of my tasks, but to refute the part of me that works hard to prove I am not a slur.

The poignant slurs that go along with being a woman are often associated with being The Other Woman, an archetype that is the bane of all the goodness in relationships. The Other Woman is alluring, secretive, provocative, vulgar, and most importantly, difficult for men to deal with and society to box-in. Women who are “taken,” are safe from this assumption, but all else must prove they aren’t alluring in any way, as aforementioned.

Perhaps marriage was never the problem, or monogamy, but generational guidelines for these things, and the thought that love is the ultimate Olympus. The pressure that is put on marriage and love to be the sole fulfillment in life is deep rooted in women’s roles and construes the whole point of the act, which is understanding and unguarded love, or something along those lines. On top of that, the pressure on women when they qualify as“other” to be taken and no longer under constant moral interrogation squanders the margin of error for many relationships, and leads to many women staying put if only to prove loyalty and good moral character, effectively avoiding the inevitable, “what did she do to deserve it?” if a relationship fails.

Black and white thinking around women’s archetypes has a notoriously thin line and it drives more than we often gauge; movies, books, and shows often have a very distinct heroine who is the opposite of the other woman. It influences how we act, what we wear, how many male friendships are suspicious, and how we react to certain situations. For example, in a recent lesson in psychology the class was given two situations about two women who were in very similar situations; both by an unfortunate turn of events were murdered, but one was a widow and one was the other woman. Unsurprisingly, when every student took the survey determining how guilty each person was for the way their lives ended, the widow was blameless, while most people seemed to think the other woman was responsible for her own death, almost as much as the actual murderer. The lesson was that, in this world, we often think people get what they deserve, i.e. “The Just World Hypothesis,” it justifies any injustice a perceived promiscuous woman gets because she deserves it.

But there’s one thing misogyny didn’t account for: what if we owned these words and didn’t try to prove anything? As seen in the self proclaimed “bimbocore” that popularized in the past few years, which takes the derogatory word from the early 2000s synonymous with dumb blondes and gives the word a distinct nuance that says “yes I like pink, yes I’m blonde, and maybe I don’t have a profitable skill, but I own it.” It directly argues hustle culture and the need for all people to equal profit, and takes the archetype and makes it distinctly bubble pop feminist, reclaiming the term for the girls.

It’s crucial in this age of change, to stop taking a woman’s relationship status, and applying it to their personality. Archetypes are useful, but at the end of the day are often not applicable to real life. I was recently told by a close friend on a random morning at the library that she wouldn’t be surprised if I had a secret life or lover, and I smiled despite myself, caught off guard by the casual inquiry so soon after breakfast, and doing a small justice for myself, neither confirmed nor denied, knowing that my private life would remain ambiguous to most. Secrets were like jewels that grew more lustrous the longer they were kept, and the more I kept to myself the more I knew myself, this shouldn’t be as controversial as it often is, women believe it or not, should be allowed to be private without speculation. With most people having their entire lives on social media, being “secretive” means having a distinct personal life (something not overtly sinister), and worse the declarative nature of having most relationships on public accounts reinforces that “other” or “taken,” trumps all else in a new era. Currently I find myself in a renaissance of freedom, I am under no obligation to share my life, no obligation to prove I am a “good girl,” and am embracing every contradiction with open arms. I encourage other women to look at their lives in a similar light, and during Women’s History month, question societal “taboos,” more than ever.