Electric Buses Are Arriving in the Southcoast

One of Highland’s electric school bus chargers in Beverly, Massachusetts.

The familiar groans and fumes of a diesel-powered school bus might disappear from local school districts. In October, the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean School Bus Program sent federal grants to all 50 states, hoping to kick start a national shift to low-emission vehicles. Five Massachusetts districts received grants, including New Bedford and Fall River. The EPA prioritized giving funds to schools in lower-income areas, where buses are the more popular form of transportation.

New Bedford received $5,530,000, which adds up to 14 electric buses, and Fall River’s $3,895,000 can purchase 11 buses. However, the award also allows schools to buy “eligible infrastructure,” meaning the money could instead go to other sustainable initiatives – or it doesn’t have to be used at all.

A Beneficial Community Initiative

The advantages of electrifying school bus fleets for these cities and their students is clear. In a presentation for the Massachusetts Southcoast Chapter of the Climate Reality Project, Josh Williams of Highland Electric Fleets detailed the obvious and more subtle results. A prolific start-up headquartered in Beverly, Highland works nationally to electrify fleets. They worked with New Bedford and Fall River to map out a plan for purchasing EVs in the next year.

Without the constant chugging of toxic diesel fumes into the environment, the chances of children developing health issues – such as eye irritation, nausea, asthma, and sometimes even lung cancer – related to these pollutants are lowered. The amount of greenhouse gasses emitted by the vehicles will also drop. Electric drivers have claimed that the cleaner buses have improved the environment among riders; an unexpected result, the silent drive has “naturally lowered the mood and temperament” while student behavior becomes easier to monitor.

For those concerned about the conditions these buses can tolerate, Highland already has successful fleets running in Alaska and Vermont, dispelling any myths about EVs working poorly in cold weather. Highland also makes it clear that their batteries last long enough to complete 95% of routes, so there isn’t a need to worry about a bus shutting down halfway through a ride.

An electric bus costs two and a half times the price of a diesel bus, but Highland leases their buses for the same amount that purchases a diesel bus. This creates a supposed 30%-50% cut in spending. The company assists districts in setting up the necessary infrastructure, such as charging stations, where buses will be hooked up when they aren’t running their routes. Certain chargers can save schools money by feeding unused energy back to the grid. Highland also provides the training for drivers and mechanics to operate and maintain a new fleet.

Although Highland mainly collaborates with local governments, school administrations, and advocacy groups, they pledge to work alongside hometown suppliers. “We’re not here to replace any of the existing bus companies. We’re actually here to be their electrification partner,” Williams assured in his presentation. Instead of leasing buses, Highland’s model will help bus operators electrify the buses they already own and prepare their businesses for the transition. When we reached out for an interview via email with one of New Bedford’s suppliers, Whaling City Transit, we received no response.

The Dirty Road to a Clean Ride

The rollout of these grants as a part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law embodies the Biden-Harris administration’s vision for the economy. The US will seek to become a top manufacturer of vehicle batteries, therefore capitalizing off a newfound demand while increasing American manufacturing, job opportunities, and progress on its climate goals. Plus, the western US is rich with lithium, generating the added incentive of making products domestically.

A report by the US Public Interest Research Group projected that 5.3 million tons of greenhouse gasses would be removed from the atmosphere if every school bus in the nation was electric – making it no wonder why the administration (and many other rich countries) strongly promotes reducing emissions through transitioning to electric vehicles. However, there is an undercurrent of ecological harm to consider.

EV batteries are made out of several finite minerals, chiefly lithium, nickel, and cobalt. Mining for lithium, especially in abundant countries like Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, creates scenes as dirty as fracking for oil. The University of Queensland estimated mining is responsible for 100bn annual tons of waste. “Extraction and processing are typically water-and energy-intensive, and contaminate waterways and soil,” writes Thea Riofrancos for The Guardian. “Alongside these dramatic changes to the natural environment, mining is linked to human rights abuses, respiratory ailments, dispossession of indigenous territory and labor exploitation.”

The most effective way to prevent damage caused by mining is to reduce the need for new materials in the first place. Investing in battery recycling infrastructure was an unexpected requirement that governments and companies are catching onto. Recycling batteries will not only protect the habitats lithium comes from, but prevent dead batteries from ending up in massive waste piles after being sent to improper facilities.

Breaking down a lithium-ion battery for reusable parts is a complex process. Carlton Cummins, the co-founder of the battery manufacturing start-up Aceleron, explains they are “rarely designed with recyclability in mind.” However, legislation has been passed in the EU that not only mandates new batteries must contain a certain level of recycled materials by 2030, but manufacturers to build collection/recycling facilities. The laws aim to extract 70% of lithium and 95% of cobalt, copper, lead and nickel from completely dead batteries. The US lacks federal policies enforcing battery recycling; the Strategic EV Management Act passed in the Senate but is currently at a stand-still.

Winning Over Non-Riders

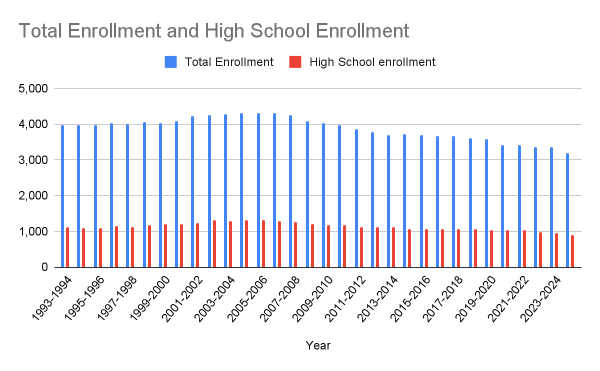

In spite of these production factors, prioritizing public transportation in general will lead to a cleaner environment. America is a country built for personal vehicles, and the distaste for supposedly dirty and unreliable bus lines has leaked into the perception of school buses. RealClearEducation reports that across the nation, 3.8 million students stopped riding the bus between 2012 and 2019. COVID-19 sustained that decline, caused by a bus driver shortage (and the general concern of putting a child in a vehicle with 20 other kids during a pandemic).

Dartmouth has no grants or current plans to purchase electric buses. However, since there isn’t a major obstacle to personal transport in our town, there is relatively no incentive for riding the bus. A junior or senior could trudge through the rain to the top of their street at 6:30 in the morning and sit for a half an hour ride. Wouldn’t they rather sleep in later and drive themselves in the comfort of their own car, even if they have to fork out a parking fee? (Is DHS’s parking fee itself a disincentive to promote bus riding?) In fact, the same reason came up time and time again when DHS students were asked why they didn’t ride the bus: it arrives too early.

Highland highlights the statistic that “students riding clean buses have 8% less absenteeism than students riding diesel buses.” This doesn’t take into account that for towns with less inclination to transition, the health benefits aren’t enough to form a better student. They also need to sleep. School start times, however, is another conversation in and of itself.